5

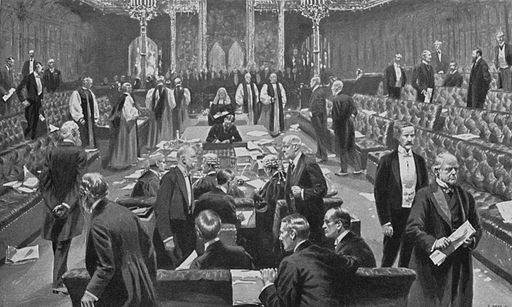

STRUGGLES BETWEEN LORDS AND COMMONS

For many centuries Britain had a bicameral Parliament in which both Houses wielded real power. At a time when the aristocracy and landed magnates were considered to be the natural leaders of the country—or at least took this role—it made sense for them to have their separate House. But as the nineteenth century moved more and more towards democracy, the role of an unelected, hereditary assembly became problematical. If the legislative power was invested in the people, as expressed in their elected representatives, what need was there for a House of Lords? Justifications generally stressed the value of review by a body of men, often experienced in government, who were not subservient to passing electoral fads. But it might be that, to secure their continued existence, they would have to either change their makeup to better reflect the nation, or accept limitations on their role in legislating.

Only a few feeble gestures were made to alter the membership of the House of Lords during Victorian times: the acceptance of three law lords who would not become part of the permanent aristocracy, and the enlargement of that aristocracy with more individuals from commerce and manufacturing (see Part 1 Sec 2, The Creation of New Peers). The decisive steps were taken later in the twentieth century: in 1958, when the Life Peerages Act made it possible to make lords and ladies of commoners who hadn’t the means to sustain a hereditary peerage; and 1999, when the House of Lords Act removed all but 92 hereditary peers and made it a chamber predominantly of those life peers. But meanwhile the diminution of the Lords’ powers was achieved in 1911, when the Parliament Act curbed their ability to delay or reject legislation passed by the Commons. The way to this reform was paved by struggles between the two Houses throughout the Victorian period.

The First Reform Act of 1832 did not establish the Commons’ supremacy, but it did put a brake on the Lords’ power by the way it was passed. The majority of peers bitterly opposed the measure, which did away with various “rotten boroughs” and pocket constituencies, virtually belonging to them, which allowed them to control the House of Commons as well as the House of Lords. After a fifteen-month roller-coaster of political manoeuvres, rioting, and mass meetings, the Lords were finally induced to pass the third version of the bill by King William’s reluctant agreement to create as many new peers as would be necessary to ensure its passage.

A certain number of new peers of liberal persuasion could have been harmlessly appointed from the sons of existing peers, or non-representative Irish or Scottish peers, or childless older men whose title would become extinct on their death. But the number needed here—up to 50—would have meant diluting the peerage permanently with a different class of men. This threat hung over the Lords’ heads thereafter. It was never used, but the possibility was a decisive factor in leading the Lords to assent to the Act that muzzled them in 1911. It gave them the experience of being unable to resist an overwhelming public pressure.

Some commentators say that, in the period between the first and third Reform Acts (1832 - 1884), the Lords were wary of being too confrontational.1 They did not want to provoke calls for the reform or abolition of their House, or for a new class of peers to be introduced. Thus, on the urging of the Duke of Wellington, they swallowed some bitter pills such as the Municipal Corporations Act (1835) and the repeal of the Corn Laws (1846). The Duke’s conduct was often invoked thereafter as a model of sensible accommodation.

But other commentators stress that they were far from being cheerfully cooperative. According to Norman Gash, they persistently rejected, mutilated, or delayed many Whig measures.2 Even proposals from a Tory government could sometimes encounter difficulties.3 An unsympathetic historian, James Wylie, has a terrific list of the reforms they tried to block, including the admission of Jews to Parliament, the complete admission of nonconformists to universities, the abolition of compulsory contributions to the Church of England, the opening of graveyards to nonconformists, the secret ballot, the sale of army commissions, the prohibition of child-labour in mines, the education of pit-boys, the right of married women to own property, compensation for ejected Irish tenants, and almost any other proposal that might have pacified Ireland.4

It is probably hard for an even moderately liberal modern reader who sees merit in these measures to believe that the lords had the good of the country in mind, rather than the preservation of their own aristocratic privilege. But they considered them to go hand in hand. One point that leaps out from reading their debates is the innate conservatism of the majority of lords. To them it was a duty to uphold the existing social fabric. The country gentleman, the Church of England vicar, the well-connected army officer, the Eton graduate: men such as these were the backbone of a successful nation. “Democracy” (a pejorative term) meant dislodging them in favour of ignorant masses, and risking all the ills of the French Revolution. Religious conservatism centred around the maintenance of Britain’s Christian character. A favourite dictum was that of the former Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke, “Christianity is part and parcel of the English Constitution.” This conservatism was increasingly directed towards keeping Ireland in the United Kingdom.

The constitutional function of the House of Lords was envisaged in these terms. The lords’ oversight was necessary to make sagacious changes to the often over-hasty legislation of the popular assembly. They provided a brake on the wild and untried enthusiasms of temporary majorities in the Commons, and a voice for caution—necessarily on the side of conservatism, because it is not easy to change things once destroyed.5 To shirk these duties would mean becoming a mere rubber stamp to the Commons, and hence expendable. On the other hand, they might also be considered expendable if they routinely frustrated the elected members of Parliament, who were increasingly seen as the voice of the nation. So, many debates involved the question of how far they could safely go in opposing Commons bills.

A good example of the conservative leanings of the House during this period is their hostility to the admission of Jews to Parliament, which involved removing the words “on the true faith of a Christian” from the oath MPs were required to swear. Many “Jew bills” had been passed by the Commons during the 1830s and 1840s, only to be defeated in the Lords, but the decisive bill was introduced in late 1857 some years after the election of the Jews Lionel Rothschild and David Salomons in London: originally a Liberal measure, but inherited by the Derby government. In the spring of 1858 it obtained second reading in the Lords, but faced a huge struggle in the committee stage.

One might think that the opposition was simple antisemitism, and not really the Lords’ business since it concerned admission to the House of Commons. But to some of the lords it was making a stand to defend the Christian basis of the British Constitution. The Earl of Clancarty saw ruin in allowing those “who deny Christ and reject the divine laws” to frame legislation, and in giving a Jewish MP the freedom “to operate, if he so chooses, not only against the Protestant Church, but for the overthrow of Christianity itself.” Viscount Melville deplored opening a gate that “would give admission to Jews, Turks, infidels, or heretics.” Lord Berners foresaw that “if one Jew were admitted to sit as Member of the Legislature, neither their Lordships’ House nor the monarchy would be longer safe.”6 Only a minority of lords stressed fairness, civil rights, and the sterling and unthreatening qualities of Jews.

Eventually the Lords struck at the heart of the bill by passing an amendment that defeated its purpose. The House of Commons studied their response in a committee that comically included Rothschild himself, who as an unsworn MP was permitted to do most things except vote on measures; they rejected the changes. In this case a compromise was eventually reached, allowing each House to decide on an appropriate oath by resolution. The bill became the Jews Relief Act of 1858. For 16 years thereafter Rothschild sat in the Commons where, according to his Oxford DNB entry, he never once spoke. Christianity and the monarchy remained intact, and no Turks appeared.

A later defence of Christianity in its particular Church of England form is seen in the Universities Tests Act of 1871, a Gladstonian measure, which also illustrates eventual capitulation by the Lords. Though Oxford and Cambridge were traditionally closed to all but those who would swear to the 39 Articles of the established church, dissenters had been admitted for a BA in 1854 and 1856 respectively. But only Anglicans could obtain an MA, or be appointed to a university office. This bill proposed to abolish all such tests and democratize the universities. It easily passed the Commons, then went to the Lords, where Salisbury was the chief objector. As Chancellor of Oxford University, he felt it his mission to keep orthodox Christianity at the centre of education, and to fight against unbelief. He therefore proposed various amendments, the chief being a new test for tutors, who must declare that they would teach nothing that was contrary to the Bible. Most bishops agreed.

The Lords sent the bill back to the Commons with this and several other amendments reimposing religious requirements. Nevertheless, when the Commons rejected the amendments and Salisbury moved to insist on them, he was defeated. Perhaps the Lords were swayed by the fact that the Commons had disagreed without even troubling to divide, so unanimous were they, whereas the Lords vote had been close. At any rate, the final vote to accept the Commons version was a convincing 129 to 89.

Another facet of the conservative outlook can be seen in the Lords’ opposition to Gladstone’s 1871 Army Regulation Bill, which abolished the selling of commissions in the army. This practice had actually been illegal since 1809, except when regulated by a royal warrant fixing fair prices. But, successive warrants being issued, the upper classes would often purchase a position for their younger sons, who could eventually sell it to fund their retirement. The Liberals contended that this “spider’s web of vested interests”7 hampered Cardwell’s army reforms at every turn. Opponents almost all agreed that purchase was hard to defend in principle.8 Yet “no other proceeding in the ministry aroused a more determined and violent opposition” in both Houses than this attempt to replace it with selection by merit through competitive examinations.9

The argument from conservative principles was that the scheme, though faulty, had served the British army well. “It is not safe to rush into [abolition] with excessive haste,” said the Earl of Dalhousie, supporting the Duke of Richmond’s resolution not to proceed with second reading until they saw a comprehensive replacement plan. The closest to an admission of a class interest in purchase came from the Earl of Carnarvon, who suggested that, with selection, “First a gentleman and then an officer” would be replaced by “first an officer and then he may or may not be a gentleman.”10

This bill illustrates a novel way to circumvent opposition in the House of Lords. After the Lords had dropped the bill on July 17, Gladstone advised the Queen to sign a warrant cancelling the regulations that authorized sale and purchase. This she did on July 20, thus making all bought commissions illegal. Many lords were outraged at this menace to parliamentary supremacy, and wondered why the bill had been presented at all. But without an act of parliament, compensation could not be provided to purchasers who had paid above the regulation price. The Queen’s cousin the Duke of Cambridge, Commander-in-Chief of the Army, had taken his seat in the Lords and recommended passing the bill for this reason—though apparently, as an unwilling tool of the government, “inaudibly and without conviction.”11 Presumably this was the consideration that led the Lords eventually to consent to second and third reading.

A constitutional convention that the Lords tested during this period was the fact that only the Commons could vote supplies and control the budget – as they had done since Stuart times. Gladstone was a key figure here, fighting many battles with the Lords. He had first provoked their hostility when, as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Aberdeen coalition in 1853, he introduced a radical budget that took off certain taxes, but made up for the lost revenue by introducing a new tax on land passing by settlement. (Settlement was a legal arrangement which allowed aristocratic heirs to inherit their estates without paying duty). The Earl of Winchilsea called the Succession Duty Bill “one of the most corrupt, the most detestable, and the most odious Bills that had ever been placed upon the Statute-book.” Derby urged that, though the Commons would probably reject any amendments the Lords made to a money bill, they should try or they would become “a useless portion of the Legislature.”12 There were a few precedents in which the Commons had in effect accepted Lords’ amendments to money bills, but saved face by producing a new bill that incorporated them. However, the government was having none of it, and in the end the Lords bowed to constitutional usage and passed the unamended bill.

When Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer in Palmerston’s government there was another financial conflict, this time with constitutional ramifications. His monumental budget of 1860 removed all but 48 of 419 duties, including the excise duty on paper that made it expensive to print a newspaper or book. When the Paper Duty Bill came for 2nd reading in the Lords on 21 May 1860, Lord Granville introduced it as a means of facilitating “publications which the working classes desire and ought to obtain.”13

The lords did not overtly show themselves hostile to a popular press, but this was surely behind their otherwise unaccountably strong resistance. Lord Lyndhurst, a former Conservative Lord Chancellor now approaching his 88th birthday, used his legal expertise to advance the argument that, though it was true that the Lords had no right to amend a money bill, let alone to originate one, yet it was certainly within their powers to reject one totally. The precedents he offered were somewhat sparse, the most recent being dated 1807. Government spokesmen pointed out that these were not bills of supply, in spite of having financial aspects; moreover, whatever might be true technically, in rejection they would be acting against what the Duke of Argyll called “the very root of the constitutional usage which has hitherto regulated the relations between the two Houses.”14 Nevertheless the Lords, anxious to claim some input into financial matters, rejected the second reading of the paper-tax bill by 193 to 104.

Gladstone called this a coup d՛état,15 and argued for a vigorous defence of the Commons’ rights over supply. But he received little sympathy in Palmerston’s aristocrat-heavy Cabinet. In fact Lady Palmerston had sat in the Lords gallery, openly declaring that she hoped the bill would be rejected.16 So after passing some protesting resolutions in the Commons, Gladstone had to accept the defeat. Hanham in The Nineteenth-Century Constitution says that Lyndhurst’s speech established it as a principle that the Lords could reject, though not amend, a money bill.17

Nevertheless, next year Gladstone did an end run around the Lords by devising a new procedure. Instead of setting forth his financial plans in a budget speech and then embodying the various measures in separate bills, as was customary, he bundled them all together into a budget bill of 1861, immune from amendment by the Lords. The Lords bridled, Lord Monteagle calling it “a new mode of coercion” to which, “as a friend to the Constitution of England he was strongly opposed,” and Earl Grey seeing “a desire at all hazards to annoy the other party.”18 But they passed the bill without even voting on the amendment to reject, and this new way of presenting the budget became the norm. “The House of Lords, for its misconduct, was deservedly extinguished, in effect, as to all matters of finance,” wrote Gladstone exultingly.19 They never did reject a budget until 1909, when it proved to be their undoing.

It was odd that Gladstone became such a thorn in the flesh of the House of Lords, given that he began his political career as a staunch Tory. Particularly ironic are his two major run-ins concerning the Church of England, since he was a fervent Christian and long represented Oxford, the bastion of the High Church. But he wanted to purge the church of privileges that only produced antagonism, including its being the established church in Ireland. In resisting these reforms, the House of Lords believed themselves to be guardians of the nation’s religion. They also began to elaborate a notion of their representing the fundamental beliefs of the people that was to become more important later.

The first skirmish concerned the abolition of the compulsory collection of church rates (money demanded from one and all to repair churches). This was a private member’s bill introduced by Gladstone as a Liberal during Derby’s ministry in November 1867—so not a government “money bill”—and eventually passed by the Commons. In 1868 the Lords accepted the principle of the bill, in spite of disapproving of this first step towards the separation of Church and state – influenced, perhaps, by its adoption by a Tory government. However, they stripped out all its new administrative arrangements, leaving the machinery of the ancient vestries as it was before. In that Gladstone had to accept these changes to get the bill passed, perhaps it was a constructive compromise as Olive Anderson argues.20 The fact that Evangelicals, Catholics, and Jews were no longer forced to help repair Anglican churches was a major victory for the Liberals.

Even more significant was Gladstone’s bill, in his first term as Prime Minister (Dec. 1868 to Feb. 1874), to disestablish the Church of Ireland, a Protestant state church with about 500,000 members in an island of 4 to 5 million Catholics. A modern reader might hardly believe the tremendous antagonism this measure aroused, causing an uproar that split the nation, and cited as a momentous step for years afterwards. In Ulster, Orangemen marched with bands and banners to defend the rights of Protestants, while in Dublin Catholic Irishmen declared they would not cease their fight “while one shred of the ascendency flag flaunts its blood-red insult in the face of the Irish nation.”21 In England, Anglicans and Nonconformists both held turbulent meetings. The House of Lords, with its Bench of Bishops and establishment-minded, mainly Anglican peers, became a centre of the storm.

Gladstone’s bill passed the House of Commons on 31 May, 1869, by a majority of more than 100. In the House of Lords in mid-June, the debate on second reading went on for four days and nights, peer after peer and bishop after bishop rising to speak, even if he had never addressed the House before. Some considered the move unconstitutional, contravening the Act of Union between England and Ireland. The Earl of Clancarty, always solicitous for Her Majesty, claimed that it would require her to break her Coronation Oath. The Bishop of Tuam, making his first and perhaps last speech in the Lords (should he be expelled along with the Irish Church), urged the House to stand up boldly and avoid opening a breach in the Constitution “through which anarchy and democracy may rush in.” To the bitter end he considered the bill “a national sin.”22

While the more liberal peers stressed the fairness of the measure and the pacification that it might bring to Ireland, other lords saw in it a plot either by the Liberation Society (dedicated to tearing down all established churches), or by the Catholics, who “endeavour to level that Church in the dust, in order that they may exalt their own Church upon its ruins.” The Archbishop of Dublin spoke for many bishops when he deplored the establishment of a state without a religious foundation by “the unconsecrating of all those mysterious agencies which bind a human society.”23

Gladstone was in the House of Lords, sitting on the steps of the throne, to witness the momentous vote for second reading, which took place at 3 a.m. on June 18th in the most packed House in living memory.24 Only one bishop of 16 voted for acceptance, and the two English archbishops and many peers abstained. Nevertheless it passed by 179 to 146, many lords staking their hopes on mitigating amendments.

The committee stage involved five days of debate and painstaking dissection of the bill, and produced 62 amendments. Many were designed to obtain more money for the disestablished church. In the most contentious, the lords struck out the clause specifying that any surplus funds were not to be used for any religious purpose, but to relieve suffering. They suggested sharing a part of what was left over to provide rectories for Church of Ireland, Presbyterian, and Roman Catholic ministers--- a gesture towards religious equality which, said Lord Athlumney (an Irish peer and former Chief Secretary for Ireland), would bring “a message of peace.”25 But when the amendments were sent back to the Commons, a manic suspicion of the “concurrent endowment” of all three religions led to the rejection of this and 26 other amendments. The lords’ suggestions ran afoul of the pledges made on the hustings by some MPs that not a penny from disendowment would go to the Catholics.

The Lords hotly discussed this rebuff from the Commons on July 20th, and insisted on their amendments. This infuriated members of the public, who took up arms against aristocratic presumption; Parliament was showered with petitions from all over the country calling for “the Bill, the whole Bill, and nothing but the Bill.”26 The deadlock was broken only by private consultations between the Lords Granville and Cairns (for government and opposition) to hammer out compromises. Miraculously, all was a rare sweetness and light when the bill finally received third reading (July 22, 1869).

In the course of this debate important points were made about the constitutional position of the House of Lords. This was far from the first time it had been suggested that the Lords should not hold out indefinitely against the will of the people, but in this debate Lord Salisbury gave the doctrine a trenchant formulation that is often quoted: “the object of the existence of a second House of Parliament is to supply the omissions and correct the defects which occur in the proceedings of the first.” In other words, they were primarily a revising and delaying house, as Bagehot had recently stated in his English Constitution (1867).27

But Salisbury added an important caveat: the Lords must first ascertain “whether the House of Commons does or does not represent the full, the deliberate, the sustained convictions of the body of the nation.”28 The Commons might be legislating on a temporary wave of enthusiasm or an unstable alliance, in which case the Lords could defeat their bills with a clear conscience. They could argue that their struggle was with the Commons, not with the nation itself. “The plan which I prefer,” he wrote later, “is frankly to acknowledge that the nation is our Master, though the House of Commons is not, and to yield our opinion only when the judgment of the nation has been challenged at the polls and decidedly expressed.”29 (Incidentally, this adumbrates the modern Salisbury Convention, crafted by his grandson the 5th Marquess after the Labour victory of 1945, that the Lords will not oppose the second or third reading of any government legislation from the Commons that had been promised in its election manifesto.)

In this case, the nation had indeed expressed itself strongly for the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland. The recent election had been triggered by the success of Gladstone’s resolutions on that church while he was in opposition, and had returned a large Liberal majority. So the advice of a number of peers, including Salisbury himself, was to accept the bill in principle and to amend it in the committee stage; what Lord Stratford de Redcliffe called “correcting and improving it to the utmost of your power.” Those who argued against second reading, like the Irishman William Connor Magee, the new Bishop of Peterborough, had to contend that the nation may have voted for disestablishment, but not for the wholesale disendowment this bill proposed, which had not been spelled out at election time.30 This question of how much a party’s election victory constituted a “mandate” was to be discussed later, but at the time it seemed rather a quibble, and the second reading passed.

In the background was the notion that the will of the nation may sometimes be better expressed in the House of Lords than by elections. Just the year before, the Duke of Marlborough had suggested that it was the Lords who represented “the inner feeling of the English nation, and, perhaps, that ‘still small voice’ which counsels prudence, moderation, and delay.”31 In the present debate Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, said that this House was “in some respects more eminently representative of the nation than the other House of Parliament.”32 As some analysts have pointed out, at times this may be true.33 The House of Lords was a respected institution often consonant with the views of those who upheld the rights of those with property, education, and a “stake in the community.”

Though the Lords could not be said to represent the inner feeling of the English in this case, they did suggest some admirable revisions. Being unelected, they did not have to take account of anti-Catholic prejudice in the constituencies, but were able to support clauses of generosity towards the church and other Irish denominations. According to Lord Malmesbury, the House of Lords had “acted independently, honestly, and fairly” in speaking for a minority view.34 The hard facts of politics defeated them. Lord Cairns was not popular with his colleagues for having negotiated independently with Granville, and he resigned as Lords Conservative leader shortly after. In the end, the surplus money was used neither for religion nor to relieve suffering, but for purposes as varied as pensions for teachers, sea fisheries, and seed potatoes.35

The House of Lords may truly have been closer to the nation’s opinion than was the Liberal party in another tussle with Gladstone, over his Ballot Bills (1871 and 1872). This introduction of the secret ballot was a corollary to the Second Reform Act, to protect the newly enfranchised from the bribery and intimidation (of tenant farmer by landlord, worker by employer, union member by his peers, even shopkeeper by his customers) that were so easy when he had to declare his vote in public. But many, including most Conservatives, felt that the measure was un-English; as Lord Lyveden (a Liberal peer) put it, the secret ballot “would introduce a sneaking and a selfish suffrage instead of that open and manly expression of opinion which has given us free institutions.”36 Not a single lord complained that it would diminish his influence, or admitted that he had any. (“Talk of influencing farmers by coercion to give their votes! Does any man of sense for a moment dream of such a thing?”37 ) Still, the fact that Irishmen would probably vote for Home Rulers if not coerced by their landlords was in the back of many minds.

This was a good time for Salisbury to apply his constitutional argument that it was “our duty to regard ourselves in this matter as agents of the Nation” rather than the Commons.38 There was little sign that the nation was eager to change electoral practice. A number of MPs now supporting the ballot had been elected as opposing it, including Gladstone himself, so the notion of a mandate did not apply. When the Lords defeated the second reading of the bill of 1871, on the grounds that it had come to them too late in the long, hot summer (10 Aug.), there was no popular outcry against the Lords, and apparently no effect on by-elections.39

But when a simpler bill passed the Commons in 1872, the Conservative majority in the Lords were hesitant to follow their convictions, reject second reading, and risk a confrontation and possible dissolution. Instead they opted for Richmond’s tactic of accepting but amending the bill – including defeating its purpose by making secret balloting optional. When the Commons rejected this amendment, though accepting a few others, they narrowly voted to back down. Disraeli’s desire to avoid a premature election, possibly aversely affected by the ballot question, undoubtedly played a role.40 As for the opinion of the nation, the majority of lords had actually come to mirror their grudging sense that the measure was inevitable and should be passed.

The Lords were fairly quiescent under Disraeli’s premiership, Feb. 1874–Mar. 1880. In fact they had already shown their partisanship by passing without too much fuss the Second Reform Bill emanating from the Derby/Disraeli ministry in 1867, even though most believed that such enlargement of the electorate was dangerous and destructive. But when Gladstone returned for his second ministry, 1880--85, hostilities began to ratchet up, especially after Salisbury became Conservative Lords leader in 1881. Corinne Weston has suggested that this more assertive stance can be traced partly to Salisbury’s desire to make the House he operated in more authoritative and meaningful.41 He exhibited a marked scorn for the House of Commons, and seldom appeared there in the Peers’ gallery. Certainly he was more confrontational than the previous two leaders, Cairns and Richmond, who wanted to “husband the Lords’ diminished prestige.”42

His tactics may be seen with the Third Reform Bill of 1884. When it first came to them in July, the Lords caused a public outcry by refusing to give this popular measure a second reading unless it was accompanied by a redistribution bill. Redistribution certainly needed to come--Wednesbury, for instance, with 20,000 electors, returned one member, as did Portarlington, with 142—but the question of whether the two reforms should proceed simultaneously or consecutively led to an absurd and prolonged deadlock, with second reading held up for months. Salisbury’s main aim was to make sure the country gentlemen and tenant farmers would not be swamped in the suburban constituencies when many new voters were added. But he was also hoping to provoke a dissolution and have an election before the franchise was widened, in which case the existing electors might reject the whole scheme.

The dissolution did not happen, and in August Parliament went into a recess, during which there was an upsurge of exasperation with the Lords’ powers. John Morley had coined the useful cry, “mend them or end them,” and this was followed by a shower of speeches and pamphlets suggesting how to do this. Labouchère would repeatedly move to abolish the hereditary feature of the House of Lords, a chamber that (like Cromwell) he considered unnecessary, obstructive, and dangerous, and whose demise he hoped to hasten through his Democratic Committee for the Abolition of the House of Lords. In due time the Lords, naturally anxious not to be abolished, themselves floated some schemes of reform. Lord Rosebery and Lord Dunraven both suggested that a peerage should not provide an automatic seat, while Salisbury moved cautiously for the introduction of some life peers. Unfortunately none of these bills gained much support.43

Meanwhile Parliament reconvened in a special fall sitting in November. Eventually Queen Victoria intervened personally to suggest a meeting between the warring parties. In a series of consultations over the teacups between Gladstone, Salisbury, Northcote, and others, the proposed redistribution bill was, contrary to all normal Parliamentary procedure, viewed and vetted by the Conservatives. Only when assured of its acceptability and immediate introduction did they pass the franchise bill and avert a major constitutional crisis.

Salisbury’s intransigence had thus paid off. He had won a major victory in looking over the plans for redistribution and securing many one-member constituencies. He had shown that the House of Lords had to be reckoned with, and could influence a government even when it had a majority of 115 in the Commons. And incidentally, he had demonstrated his own pre-eminence in the Conservative party, of which he was generally acknowledged as overall head by October 1884.

The Lords’ renewed activism may be seen in the final major confrontation in the Victorian period, over Gladstone’s unsuccessful attempt to introduce Irish Home Rule (i.e. a limited amount of self-government). This controversial measure, like the Irish Church bill, caused Trump-like disruptions, rancour, and hatred—"Such strange violence in calm natures,” mused John Morley.44 It split the Liberal party into Liberal Unionists and Gladstonian Liberals. In fact 93 Liberals had joined the opposition to defeat Gladstone’s first Home Rule bill (1886), after which he lost the election. When he returned to power, his second Government of Ireland bill eventually passed the House of Commons after 82 strenuous sittings (1 September 1893).

It was a foregone conclusion that the Lords would defeat the bill. Poignantly, the mover of the rejection was the Duke of Devonshire, who had worked closely with Gladstone as Lord Hartington. He was the older brother of Lord Frederick Cavendish, the Irish Secretary who had been murdered by extremists in Phoenix Park in 1882. Like the majority of the lords, he cherished their role as the guardians of the Empire and of “the Union of the United Kingdom, which we believe was decreed by nature.” Why, asked the Marquis of Londonderry, should they be blackmailed by the bombs and murders of the Irish Catholic dissidents, and place the necks of the “loyal, industrious and law-abiding” Protestant Ulstermen under the heels of “a body of criminal agitators?”45 Besides, many lords were Irish landlords. After only four days of debate they denied the bill second reading by a whopping 419 to 41 (September 8). The number casting a vote was unprecedented, with 17 dukes, 2 archbishops, 15 marquises and the rest taking 30 minutes to process into the endlessly-filling “not content” lobby.

Constitutionally, the lords could argue that the government had no real mandate for this far-reaching measure. Gladstone’s Commons majority had been achieved through the election of Irish Home Rulers, but he had not won over the constituencies of England and Scotland. In any case, Salisbury denied that the result of a general election was sufficient to show the country’s support of a particular measure, since different electors voted to support different parts of the platform. Elaborating on his “judgment of the nation” theory, he now espoused the “referential” function of the Lords: whenever a major change was proposed, the Lords should defeat it and force an election on that one issue—even though this arguably encroached on the Commons’ sole right to request a dissolution. According to his article “Constitutional Revision” in the National Review of 1892, “[The House of Lords] alone possess the power of securing that in a great project of fundamental change . . . the nation shall be honestly consulted.”46

What somewhat vitiated Salisbury’s constitutional theory was the fact that in practice only Liberal bills were likely to be subjected to a referendum. By century’s end, the House was overwhelmingly Conservative; Rosebery lamented that only “some miserable 20 or 30 peers” represented the Liberal party even when it had a majority in the other house.47 The House of Lords under Salisbury became “the willing tool of any Conservative Opposition in the House of Commons,” or as Joseph Chamberlain put it, “a mere branch of the Tory caucus.”48

In the case of Irish home rule, however, the Lords could plausibly claim to represent the underlying feeling of a good part of the country. The vote for the bill in the Commons had been close, and it was suggested that some Liberal MPs who voted for it were counting on the Lords to reject it.49 When the Lords emerged from the Houses of Parliament after doing so, they were cheered by a large crowd who sang “Rule Britannia.”50 Gladstone wanted to dissolve and fight an election on the relations between the two Houses, but his cabinet thought this would not be a winning move; he was reduced to pointing darkly in his last speech in Parliament that there were differences of fundamental tendency between them which eventually “must go forward to an issue.”51 Likewise Rosebery wanted the next election (July 1895) to be fought on the issue of the “medieval control” that the Lords exercised over legislation, but was not supported. There was little sign now of popular discontent. “On the contrary,” said The Times, “the country was better pleased with the Lords . . . than it had been at any time for many years.”52 In the election they gave the Conservatives and their Liberal Unionist allies a large majority. We will never know whether this attempt to give Ireland some autonomy was so premature and unpopular that it could never have succeeded, or whether it could have averted years of strife and bloodshed and been the first step towards a devolved United Kingdom.

Salisbury’s 1895 win ushered in a golden age for the House of Lords. Both Salisbury as Prime Minister and the Duke of Devonshire as leader of his Liberal Unionist allies were in this House, as was Rosebery as Liberal leader until 1897. The coalition government could speedily pass legislation sent up from the Commons, much of it of a progressive nature. Only in hindsight could this be recognized as the last flare of a dying candle.

The final step lies just beyond the Victorian period, though within its extended twilight before World War I. It is too significant to omit, and provides a bookend with the First Reform Act, also outside Victoria’s reign. In 1906, as in 1830, the Liberals had come into power after a long period of Conservative domination. Between 1906 and 1910, they lost 113 of 134 divisions in the Lords,53 who—perhaps overstepping themselves—defeated many major reforms such as old-age pensions, the abolition of plural voting for property owners, and an education bill. Using Gladstone’s technique, Lloyd George then incorporated them into his budget of April 1909. In order to pay for these far-reaching social measures, he proposed a variety of higher taxes and death duties that were anathema to the landowning class.

The political drama of the next two years can be minutely followed in contemporary accounts.54 The Lords refused to pass the budget without ascertaining through a general election whether it was really supported by the nation. In that it was a money bill, providing supplies for His Majesty’s government, to oppose it went even beyond Salisbury’s referential theory. Though the Lords eventually passed the budget after an election in early 1910 that the Liberals and their Irish allies narrowly won, the Commons persisted with their Parliament Bill which had two chief clauses. The first provided “that the House of Lords be disabled by law from rejecting or amending a money bill;” the second essentially ruled that a non-money bill passed in the Commons but rejected three times by the Lords over two years, “shall become law without the consent of the House of Lords.”

In the Lords’ somewhat exaggerated view, these constituted a major constitutional change, giving Britain in effect a unicameral legislature. When they finally debated the bill, they introduced amendments to preserve some powers, for instance demanding a referendum on major issues such as Home Rule. But another election in December 1910 weakened the suggestion that the nation might not wish to curtail the Lords: it kept the Liberals in power, their majority buttressed as if by karma by the Irish MPs alienated by the Lords’ defeat of Home Rule. Asquith made it clear that he would ask King George V to create enough peers for his original bill to pass. Whereas this would have involved perhaps 50 creations in 1832, the number 500 was now thrown about. In a cliff-hanging vote of August 9 – 10, 1911, with many lords abstaining, the Lords reluctantly accepted the Parliament Act. Henceforth the House of Lords could only advise and delay, but not permanently defeat any persistently supported Commons bill. They had become by law what by custom they had often been, a revising body only.

Appendix: Recent Developments

Of the many post-Victorian suggestions and bills to alter, shrink, or abolish the House of Lords, here are the few that were passed:1949: Parliament Act shortened the time period during which the Lords could delay a Commons bill to two sessions and one year.

1958: Life Peerages Act allowed for the creation of life peers at the level of baron and also baroness—meaning that women could now sit in the House. There was no numerical limit; prime ministers thereafter created an average of about 25 a year. (See the Appendix to Part 1, Sec 2, The Creation of New Peers, for more on this.) By 1999, they constituted about 41% of a House that had swollen to 1,330.

1963: Peerage Act allowed women hereditary peeresses to sit in the House. It also allowed peers to renounce their peerage for life if they wished to be elected to the House of Commons, as did Alec Douglas-Home, 14th Earl of Home, on becoming Prime Minister. All Scottish peers were now admitted to the House of Lords, while Irish peers could sit as MPs for all constituencies, including those in Ireland.

1999: House of Lords Act, a major act of Tony Blair’s Labour government, ejected all but 92 hereditary peers in favour of appointed life peers. All the hereditaries except the ex-officio Earl Marshal and Lord Great Chamberlain were to be elected by the existing House (creating an anomaly: hereditaries elected, life peers appointed), and to serve for life. Hereditary seats were pro-rated according to the party standing at the time, and these party groups now vote to fill their own vacancies. In an ironic reversal, some excluded hereditary peers had themselves made life peers in order to return to the House of Lords. The others were permitted to stand for election to the Commons without renouncing their peerage.

2005: Constitutional Reform Act established a Lord Speaker to take the place of the partisan Lord Chancellor.

2014: House of Lords Reform Act allowed peers to retire or resign; reinforced by the 2015 House of Lords (Expulsion and Suspension) Act, it allowed Lords to be permanently expelled for non-attendance or grave crimes.

2015: Lords Spiritual (Women) Act . Women, allowed to become bishops in this year, were to be preferred to fill vacancies in the 26-member Bench of Bishops for the next ten years.

NOTES

- 1Hanham, The Nineteenth-Century Constitution, 108; E.A. Smith, The House of Lords in British Politics and Society, 1815-1911 (Longmans, 1992), 121.

- 2Gash, Aristocracy and People, 171.

- 3Emily Allyn, in Lords Versus Commons: a Century of Conflict and Compromise (thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1927; American Historical Association, 1931), gives examples from Disraeli’s premiership, such as allotments or recreation grounds for labourers (103).

- 4James Wylie, The House of Lords (Arnold Fairbanks, 1908), 169-70.

- 5Salisbury, quoted in “Lord Salisbury at Bradford,” The Times, 23 May 1895, 6.

- 65 July 1858, Hansard, vol. 151, col. 919, 921, 714.

- 713 July 1871, Hansard, vol. 207, col. 1547.

- 8 E.g. Hansard, vol. 207, col. 1694 (Duke of Cambridge, who references Earl Russell also), col. 1722 (Earl of Derby, who mentions Commons opposition also), col. 1800 (Earl of Longford).

- 9Morley, Life of Gladstone, II, 361.

- 10July 1871, Hansard, vol. 207, col. 1588, cols. 1581-2; 14 July, col.1736.

- 1114 July 1871, Hansard, vol. 207, cols. 1694-5; “Prince George, Duke of Cambridge,” Oxford DNB.

- 1222 July 1853, Hansard, vol. 129, col. 708, col. 710.

- 13Hansard, vol. 158, col. 1446.

- 14Hansard, vol. 158, col. 1465, col. 1521.

- 15Morley, Life of Gladstone, II, 36.

- 16Greville, Memoirs, 3rd part: a Journal of the Reign of Queen Victoria from 1852 to 1860 (Longmans, Green, 1887), II, 310.

- 17Hanham, The Nineteenth-Century Constitution, 172.

- 187 June 1861, Hansard, vol. 163, col. 750, col. 739.

- 19Memorandum of about 1897, quoted in Morley, Life of Gladstone, II, 39.

- 20Olive Anderson, “Gladstone’s Abolition of Compulsory Church Rates: a minor political myth and its historiographical career,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 25, issue 2 (April 1974), 193.

- 21From the Freeman, quoted in “Ireland,” The Times, 23 July 1869, 10.

- 22Hansard, 17 June 1869, vol. 197, col. 112; 22 July, vol. 198, col. 441.

- 2315 June, Hansard, vol. 196, col. 1836 (Lord Chelmsford), col. 1812 (Archbishop).

- 24Jenkins, Gladstone, 301; Morley, Life of Gladstone, II, 269.

- 255 July 1869, Hansard, vol. 197, col. 1053.

- 26“The Irish Church Bill,” Times, 15 July 1869, 5; 21 July, 11.

- 27Bagehot, English Constitution, 79.

- 2817 June, 1869, Hansard, vol. 197, col. 83, 84.

- 29Letter to Carnarvon, 1872, quoted in Oxford DNB entry for “Cecil, Robert,” from Lady Gwendolyn Cecil’s Life.

- 30Hansard, vol. 196, col. 1707 (Stratford de Redcliffe), col. 1873 (Magee).

- 31Smith, House of Lords in British Politics and Society, 125, quoting Hansard.

- 3229 June 1869, Hansard, vol. 197, col. 718.

- 33Davis, ed., Lords of Parliament, 2; Frank Dilnot, The Old Order Changeth: The Passing of Power from the House of Lords (Smith, Elder, 1911), 57.

- 3422 July 1869, Hansard, vol. 198, col. 428.

- 35Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, part 2, 432n.

- 3610 Aug. 1871, Hansard, vol. 208, col. 1279.

- 37Shaftesbury, 10 June 1872, Hansard, vol 211, col. 1451.

- 3810 June 1872, vol. 211, col. 1495 (on the second Ballot Bill).

- 39For an analysis of the debates and possible motives, see Bruce Kinzer, The Ballot Question in English Politics, 1830-1872 (PhD thesis, Univ. of Toronto, 1975).

- 40Kinzer, Ballot Question, 422.

- 41Corinne C. Weston, “Salisbury and the House of Lords, 1868 – 1895,” The Historical Journal, 25, 1 (1982), 107.

- 42“Cairns, Hugh,” Oxford DNB, accessed Dec. 22, 2020.

- 43Allyn, Lords vs Commons, 122-4, 145-50.

- 44Life of Gladstone, III, 243.

- 45Duke of Devonshire, 5 Sept., “House of Lords, Tues. Sept. 5,” The Times, 6 Sept. 1893, 4; Marquis of Londonderry, 6 Sept., “House of Lords – Home Rule Bill,” The Times, 7 Sept. 1893, 8.

- 46“Constitutional Revision,” National Review, 117 (Nov. 1892), 299.

- 47Hansard, vol. 208, col. 484 (1871); “Lord Rosebery at the Albert Hall,” The Times, July 6, 1895. 14.

- 48Hanham, Nineteenth-Century Constitution, 108-9; Joseph Chamberlain, 1884 speech, quoted in Harry Jones, Liberalism and the House of Lords: the Story of the Veto Battle, 1832 – 1911 (Methuen, 1912), 69.

- 49Earl of Donaughmore, 6 Sept., reported in “House of Lords – Home Rule Bill,” The Times, 7 Sept. 1893, 7.

- 50Lord Lexden, “’The Great Lord Salisbury’ and the House of Lords,” accessed 22 April 2023.

- 51Morley, Life of Gladstone, III, 380, 386.

- 52“Lord Rosebery at the Albert Hall,” Times, 6 July 1895, 14; “Second Home Rule Government,” Times, 14 June 1895, 9.

- 53History of the House of Lords: a Brief Introduction,” House of Lords Library, 2016, accessed Jan. 16, 2022.

- 54E.g. Frank Dilnot’s The Old Order Changeth (1911), and Harry Jones’ Liberalism and the House of Lords (1912).